Could property-linked finance be the silver bullet to propel green retrofits at scale in cities?

Scaling up green retrofits in cities through property-linked finance (PLF)

The United States isn’t exactly known for its energy frugality. But while the US may be one of the largest consumers of fossil fuels per capita in the world, it is also leading the charge in the green retrofit of buildings.

It is achieving this by leveraging an innovative financing tool known as Property-Linked Finance (PLF) or Property Assessed Clean Energy (PACE). Based on the public-private partnership (PPP) model, it allows access to affordable and long-term funding for energy efficiency upgrades, renewable energy, resilience and water efficiency improvements to buildings. Enabled by state legislation and at the local level by cities, in the US, over 353,200+ building owners have chosen PACE to fund around $15 billion in improvements to their residential and commercial properties.

This massive investment can be attributed, in part, to efforts undertaken at the local level. Many cities across the US with climate action plans that include GHG inventories and reduction targets, have adopted financial strategies of a creative and non-traditional nature to fund their climate action priorities. Currently, 39 stateshave enabled legislation that supports PACE which has gained wide acceptance in the US as a climate investment tool to incentivize building efficiency upgrades.

"Financing building upgrades through PLF is a win-win for all: greener buildings for cities, affordable finance and energy savings for building owners and a reliable investment for lenders."

Prashant Kapoor, Chief Industry Specialist, climate Business Department, IFC

The PLF success story can be replicated by cities in emerging markets too

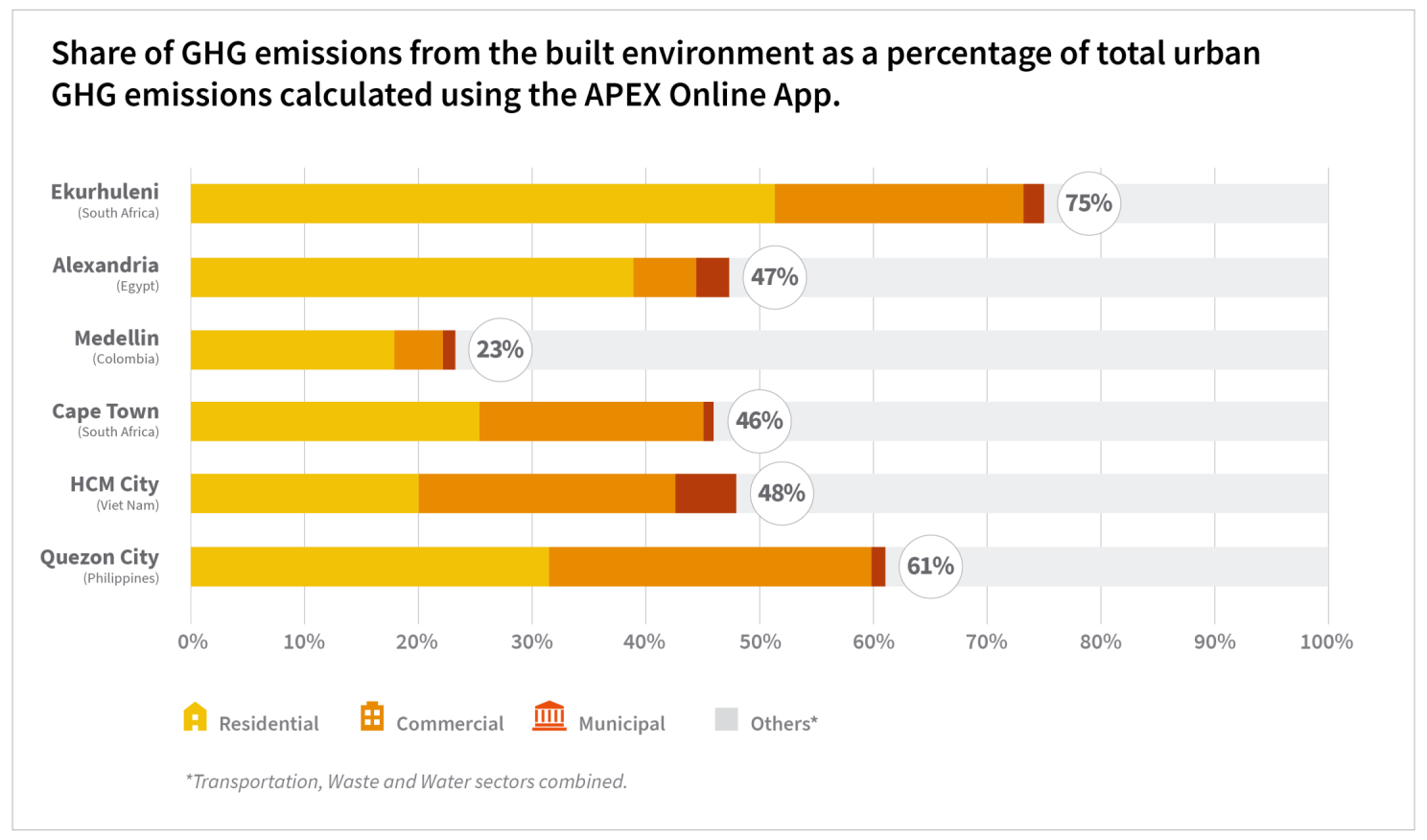

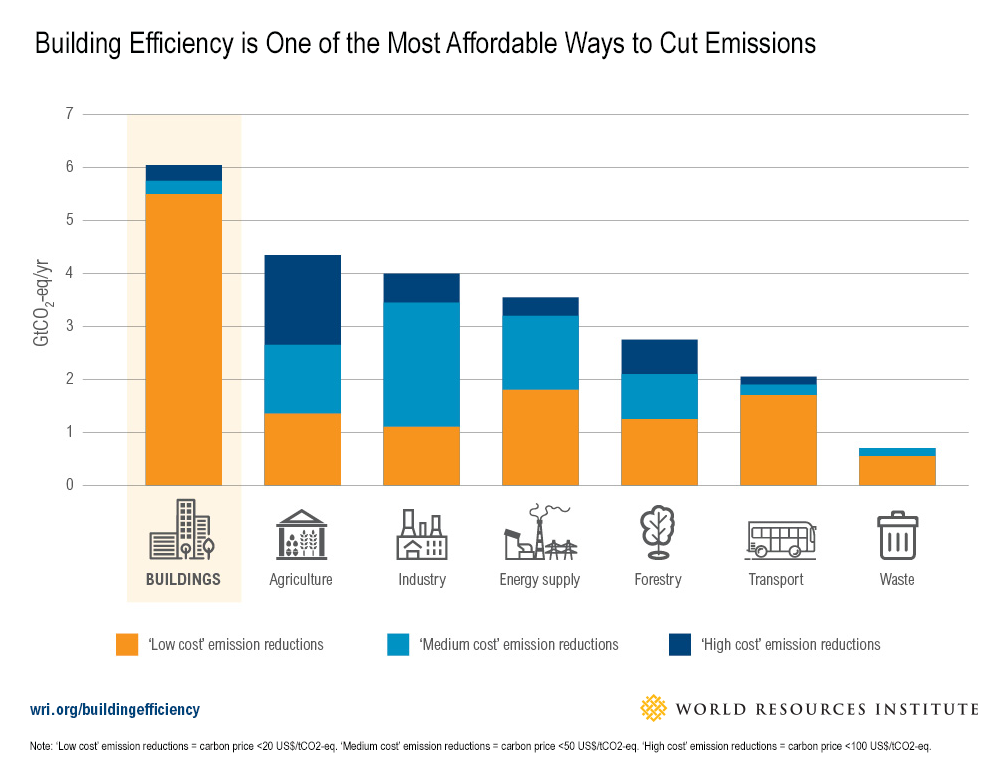

Aligning with the 2015 Paris Agreement, cities in emerging markets are developing climate action plans that focus on key sectors such as energy, transportation, waste and water to curb GHG emissions. As the graph below demonstrates, the built environment is responsible for a substantial share of GHG emissions in cities and, therefore, offers a proportional opportunity for reduction.

In addition to playing a key role in achieving decarbonization goals, retrofitting existing buildings presents a sizeable investment potential of approximately US$3 trillion globally. According to IFC’s recently published report, Building Green: Sustainable Construction in Emerging Markets, the retrofit market is estimated to have grown at a compounded annual growth rate of 8 percent from 2018 to 2023, mainly driven by demand from high-income economies. In emerging economies, however, the dissemination and adoption of retrofitting practices, especially deep retrofitting, remains limited because of the high costs of replacing energy inefficient mechanical and electrical systems, and modifying building envelopes. A September 2022 report by IEA pegs the current retrofitting rates for existing buildings at around 1 percent, most of which are low-cost upgrades that don’t make a significant dent in achieving the sector’s decarbonization targets for 2030 and 2050. However, the good news is that uptake of deep building renovations is on the rise.

Buildings need to be upgraded with high-impact measures to meet cities’ ambitious decarbonization targets

Buildings usually have a long operational life with retrofit cycles occurring every 10-15 years. Building Green: Sustainable Construction in Emerging Markets report notes that given the long operational life of a typical building, retrofits deliver similar or even higher energy savings than the construction of new green buildings. While energy efficiency upgrades such as LEDs can reduce energy use by a quarter, “deep” energy retrofits such as installation of solar panels, high-efficiency boilers and chillers, roof replacement, façade and HVAC upgrades etc., can cut energy use by more than half. Building upgrade projects need to include deep measures to have a higher impact in terms of GHG emissions reduction.

This means increasing both the quantity and quality of upgrade projects. For instance, a global green building certification system such as IFC’s EDGEmakes green building upgrades (and that of new construction) more accessible, faster and easier through a free software application that identifies the most cost-effective options for verifying building resource efficiency.

A financial mechanism like PLF can help cover the high upfront costs of energy efficiency retrofits and yield immediate payback, incentivizing owners to opt for the most effective measures. Moreover, since it is difficult for cities to regulate existing buildings, a program like PLF provides the perfect framework to support cities’ decarbonization goals. Upgrading buildings to energy-efficient standards also reduces resource use, keeps cost of operations down, increases property value, and creates job opportunities. All of these factors contribute to improving a city’s brand value.

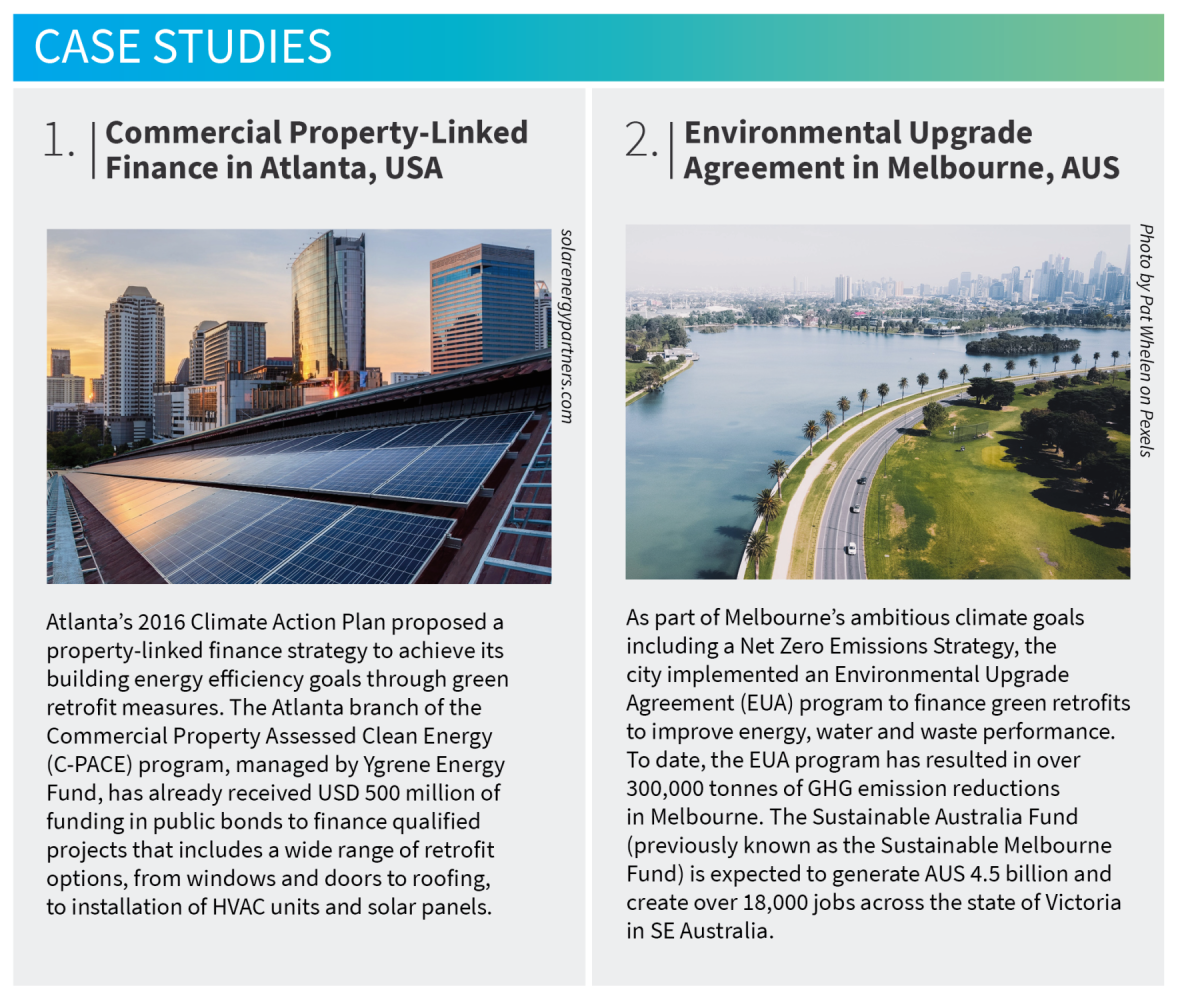

Atlanta and Melbourne are two cities harnessing this market opportunity by successfully implementing PLF programs for energy-efficient building upgrades.

Supporting green retrofits is one of the easiest ways for FIs to finance significant emission reductions

Improving energy efficiency of existing buildings is one of the easiest ways for cities to lower GHG emissions because green retrofits deliver a long economic lifespan and reliable ROI . This, in turn, makes it an attractive proposition for investment.

Cities can nudge the green retrofit market through property-linked finance (PLF)

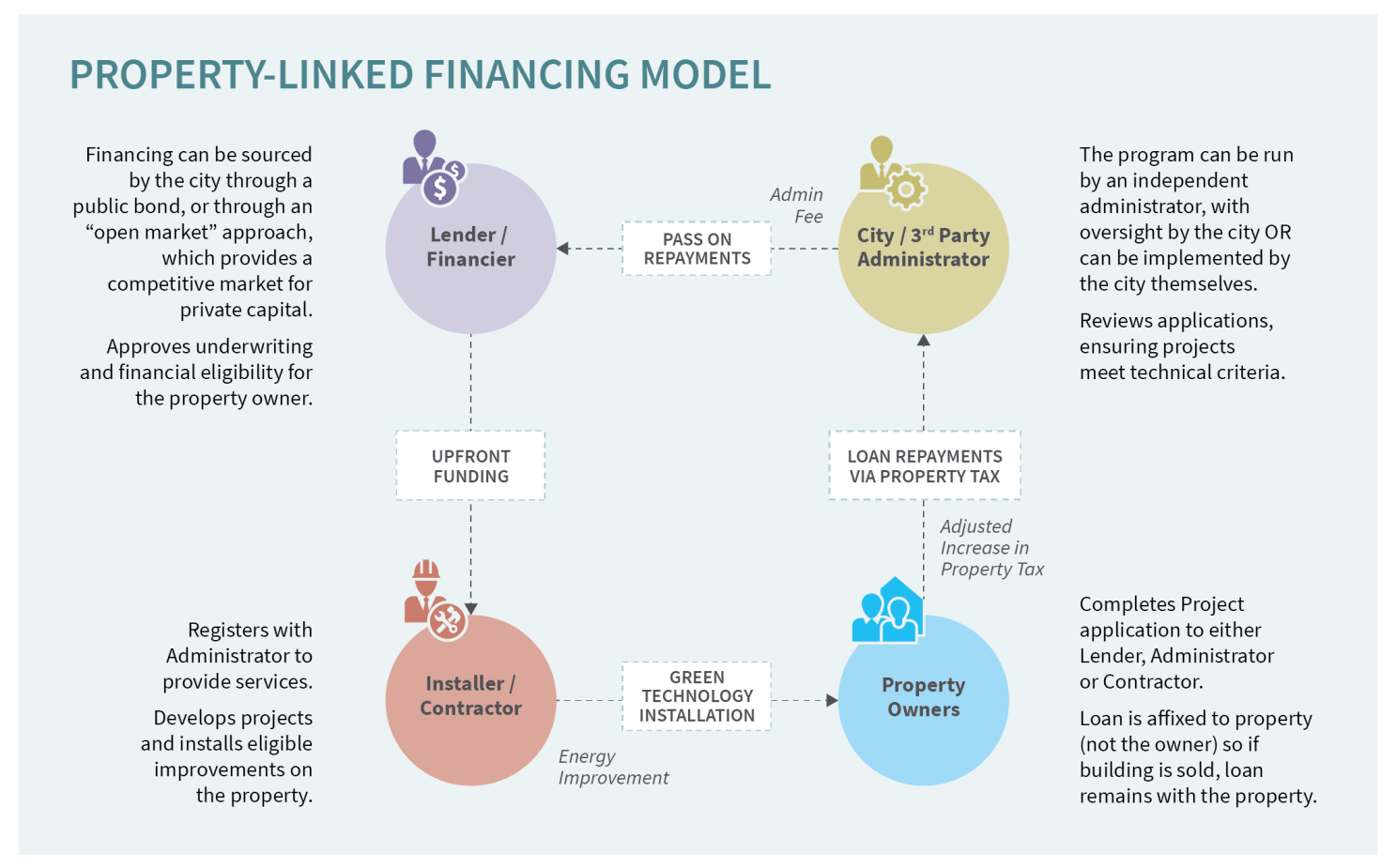

PLF is one of the mechanisms that can overcome the barriers associated with at-scale pursuit of high-impact building retrofits in cities. PLF finances up to 100% of the installation cost upfront through financial institutions (banks), which is then paid back by the property owner to the city through increased property tax over a long-term period (20 – 30 years). The monthly utility savings from the upgrades compensates for the increase in property tax.

PLF supports long-term funding of energy efficiency improvements, renewable energy and water savings in existing buildings. The borrowing is not technically a loan but a lien against the property because it is set up as an assessment through the building’s property tax. The loan is attached to the building and not the owner (or occupant); so if the building is sold, the loan remains with the property.

The operation of a typical PLF mechanism is summarized in the figure to the right.

Providing owners with capital to pay for upfront costs of green retrofits, the loan is paid back through a nominal increase in property tax, at a set rate for an agreed-upon term. Energy-cost savings deliver monthly savings for the owner, even after paying back the borrowed amount via the property tax increase. PLF enables the shift of energy efficient building upgrades from CAPEX to OPEX projects, making them more palatable, attainable and impactful to implement with zero upfront cost to the owner.

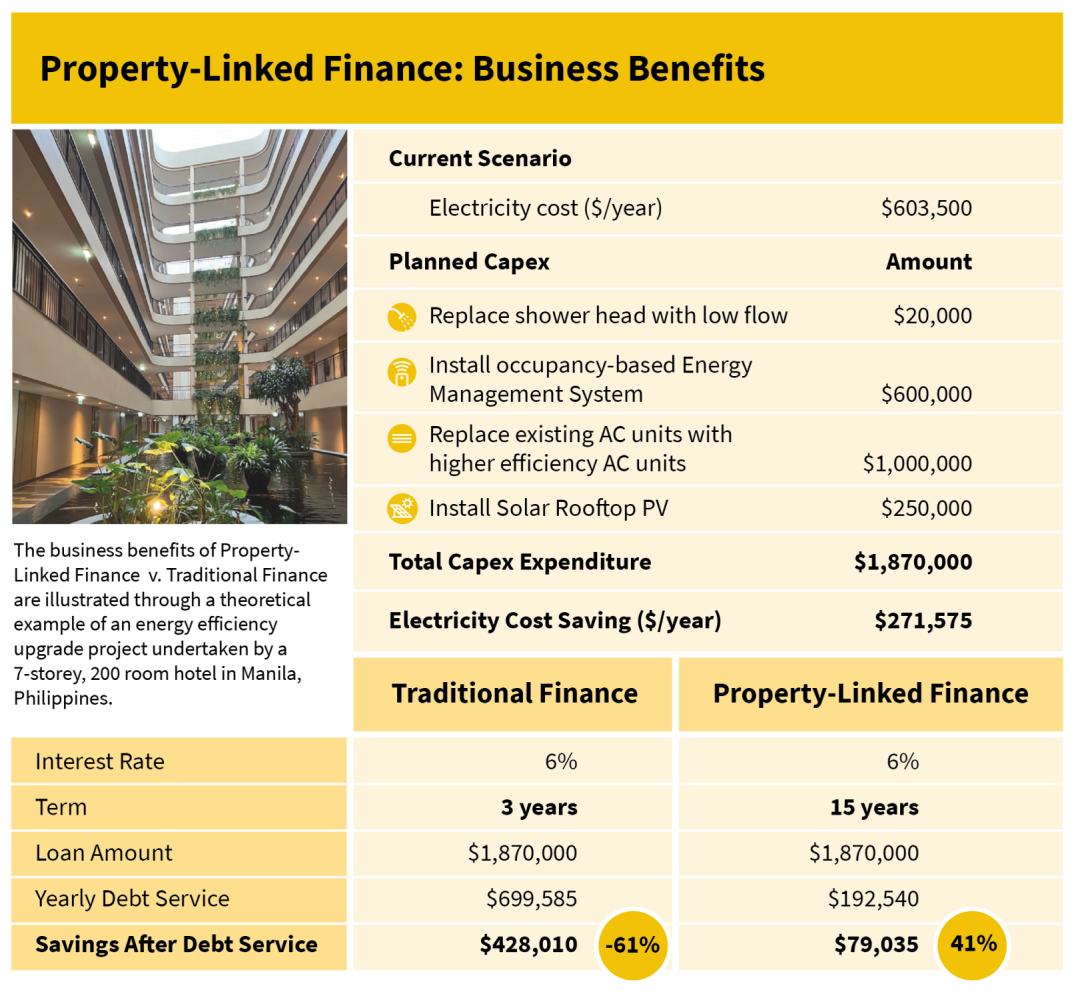

The business case for PLF speaks for itself: where traditional finance mechanisms would fail owing to the compressed nature of the payback over a shorter-term, PLF incentivizes building owners to pursue high-impact upgrades with more immediately visible results and low-to-no risk for the lender and the owner because the loan stays with the property.

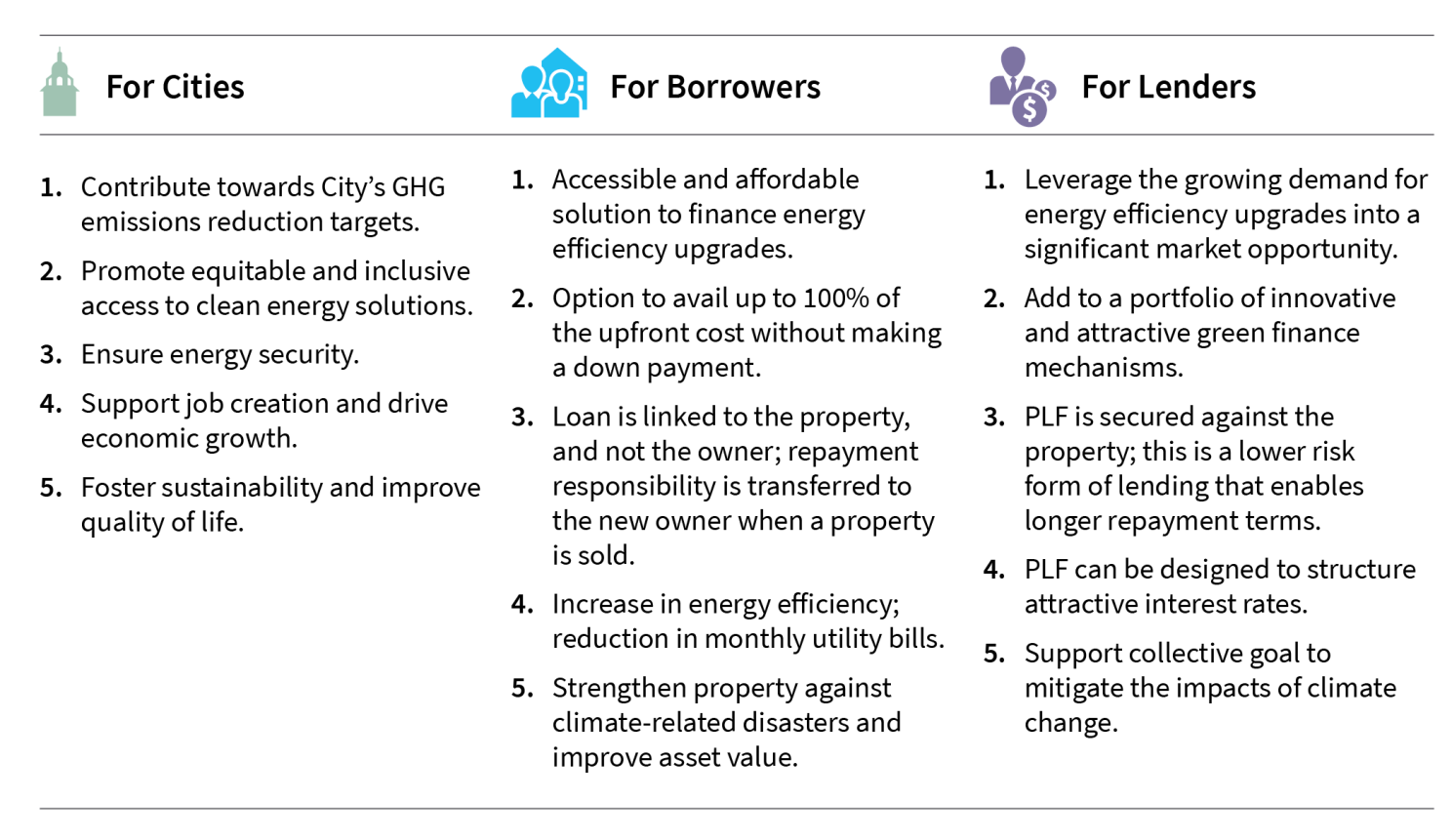

Financing building upgrades through PLF is a win-win for all

When managed correctly, PLF is a win for all: greener buildings for cities, affordable finance and energy savings for building owners and a reliable investment for lenders.

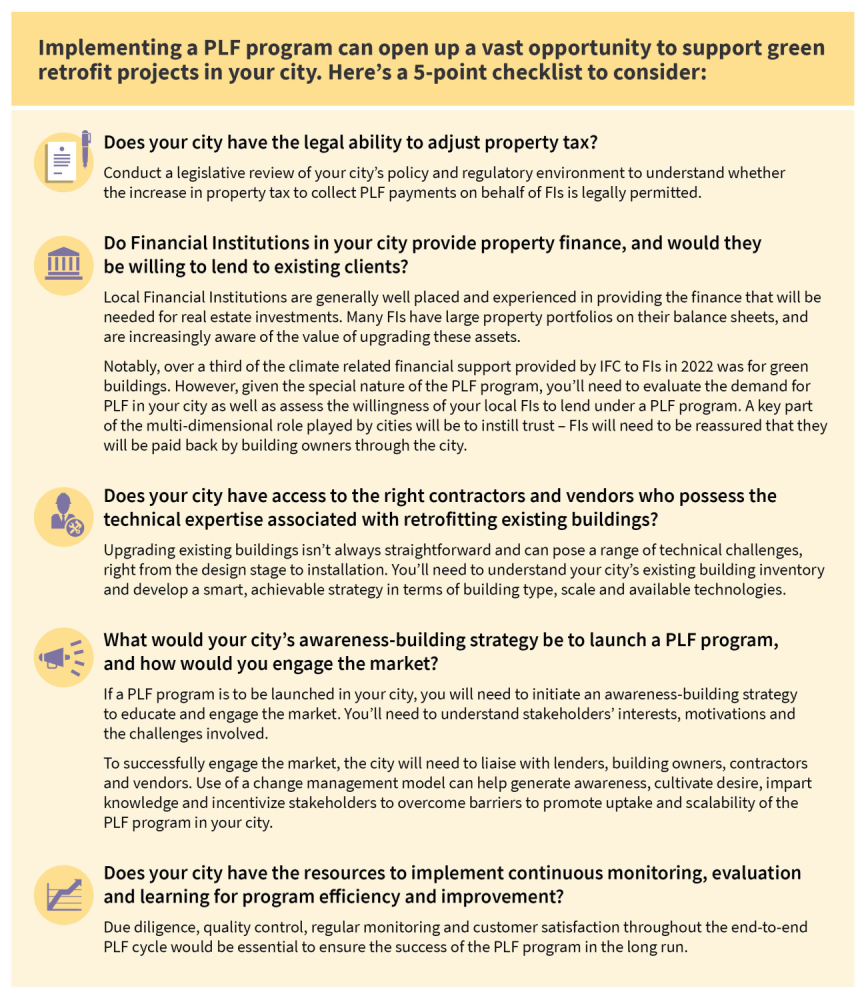

Cities can lead the charge to tap into the vast potential of the green retrofit market

Implementing energy efficiency at scale in the built environment continues to prove challenging owing to diverse stakeholders and their varied, and at times, conflicting interests. Building owners are often unable to support implementation on their own – innovative retrofit technologies are either inaccessible or unaffordable, and the increased financial responsibility is a deterrent. Financial Institutions too require legal and regulatory support – they also need a low-risk market to cater to. Visionary city leaders are in a pre-eminent position to drive a program like PLF that binds all stakeholders within a stringent policy and regulatory framework with the unified goal of mitigating climate risks and amplifying positive impacts so that green retrofits can flourish at scale.

Originally published to LinkedIn by Prashant Kapoor on January 17, 2024.